What is a Reward Model?¶

Your SFT model can follow instructions. But it doesn’t know which of its responses are actually good.

After Supervised Fine-Tuning, the model learned to mimic the training examples. But what if there are multiple valid responses? What if some are helpful while others are really helpful? The model has no way to distinguish them.

Reward models solve this.

A reward model is a neural network that predicts human preferences. You give it a prompt and a response, and it outputs a number (a “reward score”) that indicates how good that response is.

The math:

Where:

is the prompt (the user’s question or instruction)

is the response (what the model generated)

is the reward model (parameterized by weights )

means it outputs a real number (the reward score)

Higher score = better response.

Why Do We Need Reward Models?¶

Here’s a thought experiment. Rate this essay on a scale of 1 to 10.

Hard. Is it a 7? Maybe an 8? What’s the difference between a 7 and an 8 anyway?

Now: I give you two essays and ask which one is better.

Much easier. You can just compare them directly.

Humans are better at comparisons than absolute ratings. This insight is the foundation of reward modeling.

After SFT, your model can follow instructions. But it doesn’t know:

Which of two valid responses is better

How to balance competing objectives (should I be maximally helpful, or play it safe?)

What makes a response exceptional vs just acceptable

We teach the model human preferences by showing it comparisons:

“This response is better than that one”

“This response is better than that one”

“This response is better than that one”

The reward model learns from these comparisons. Eventually it can predict. for any prompt and response. How much a human would like it.

Then we use that reward model to further train the base model. But that’s RLHF, which comes later.

First: building the reward model itself.

The Bradley-Terry Model¶

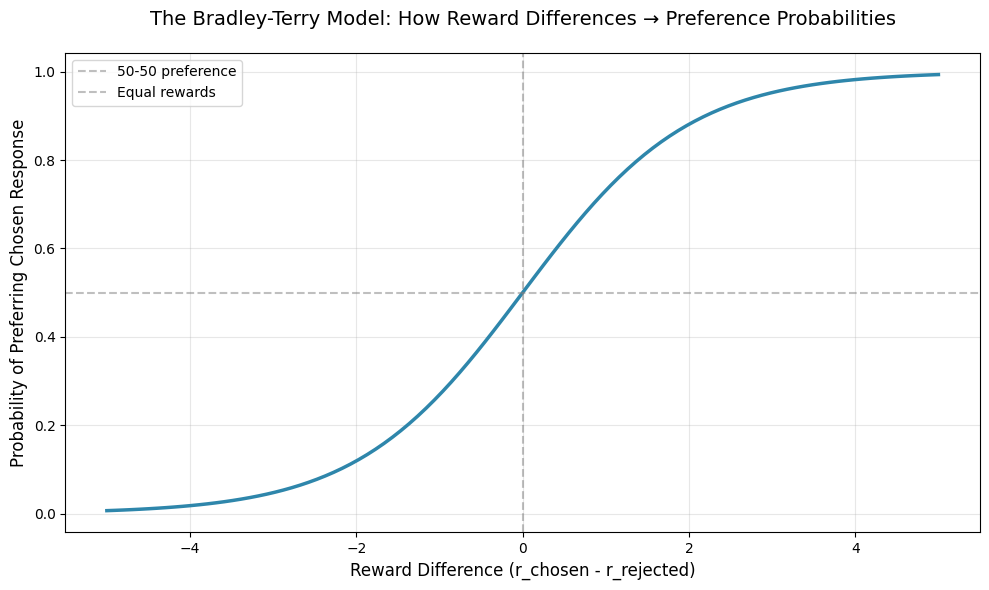

We need a way to convert reward scores into preference probabilities. Enter the Bradley-Terry model.

This is a classic model from the 1950s developed by Ralph Bradley and Milton Terry for ranking things when you only have pairwise comparisons. Think chess rankings, or comparing sports teams.

The idea: if I show you two responses. call them “winner” and “loser” based on human preference. the probability that a human prefers the winner is:

Breaking this down:

means “probability of...”

is the winning response (the one humans preferred)

is the losing response (the one humans rejected)

reads as “ is preferred to ”

means “given prompt ”

is the sigmoid function

is the reward score for the winning response

is the reward score for the losing response

So: “The probability that the winner is preferred over the loser equals the sigmoid of the difference in their reward scores.”

Why sigmoid? Because we need to convert a difference (which could be any real number) into a probability (which must be between 0 and 1).

How it works:

If the reward difference is large and positive (winner scored much higher), sigmoid outputs close to 1.0

If the reward difference is zero (both scored the same), sigmoid outputs 0.5 (50-50)

If the reward difference is large and negative (loser scored higher. the model got it wrong), sigmoid outputs close to 0.0

import torch

import torch.nn as nn

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

# Visualize the Bradley-Terry model

reward_diff = np.linspace(-5, 5, 100)

prob_prefer_chosen = 1 / (1 + np.exp(-reward_diff)) # This is the sigmoid function

plt.figure(figsize=(10, 6))

plt.plot(reward_diff, prob_prefer_chosen, linewidth=2.5, color='#2E86AB')

plt.axhline(y=0.5, color='gray', linestyle='--', alpha=0.5, label='50-50 preference')

plt.axvline(x=0, color='gray', linestyle='--', alpha=0.5, label='Equal rewards')

plt.xlabel('Reward Difference (r_chosen - r_rejected)', fontsize=12)

plt.ylabel('Probability of Preferring Chosen Response', fontsize=12)

plt.title('The Bradley-Terry Model: How Reward Differences → Preference Probabilities', fontsize=14, pad=20)

plt.grid(True, alpha=0.3)

plt.legend()

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

print("Understanding the curve:")

print("=" * 60)

print(f"When reward difference = 0: P(prefer chosen) = {1/(1+np.exp(0)):.2f}")

print(" → Both responses equally good, 50-50")

print()

print(f"When reward difference = +2: P(prefer chosen) = {1/(1+np.exp(-2)):.2f}")

print(" → Chosen response scored 2 points higher, 88% confident")

print()

print(f"When reward difference = -2: P(prefer chosen) = {1/(1+np.exp(2)):.2f}")

print(" → Chosen response scored LOWER. Only 12% confident.")

print(" → The reward model is making a mistake here.")

print()

print("The sigmoid squashes any difference into a probability.")

Understanding the curve:

============================================================

When reward difference = 0: P(prefer chosen) = 0.50

→ Both responses equally good, 50-50

When reward difference = +2: P(prefer chosen) = 0.88

→ Chosen response scored 2 points higher, 88% confident

When reward difference = -2: P(prefer chosen) = 0.12

→ Chosen response scored LOWER. Only 12% confident.

→ The reward model is making a mistake here.

The sigmoid squashes any difference into a probability.

Reward Model Architecture¶

How do we actually build this thing?

A reward model is a language model with one addition: a value head.

Here’s the architecture:

Input: [prompt] [response] ← Concatenate these together

↓

┌─────────────────────────┐

│ Language Model │ ← Start with a pre-trained model

│ (GPT, LLaMA, etc.) │ (often the same one you used for SFT)

└───────────┬─────────────┘

│

Get the hidden state of the last token

(this vector "summarizes" the whole sequence)

│

↓

┌─────────────────────────┐

│ Value Head │ ← A simple linear layer

│ (Linear → Scalar) │ (this is the only new part)

└───────────┬─────────────┘

│

↓

Reward ScoreThe language model reads the prompt + response and builds up a rich understanding of what’s happening. Then the value head (usually a single linear layer) converts that understanding into a single number: the reward.

You can either:

Freeze the base model (only train the value head): faster, but less expressive

Train everything: slower, but the base model can learn to extract features specifically useful for predicting preferences

Most people train everything.

from transformers import AutoModel, AutoTokenizer

class RewardModel(nn.Module):

"""

A reward model for predicting human preferences.

Takes a prompt + response, outputs a scalar reward score.

"""

def __init__(self, base_model, hidden_size, freeze_base=False):

super().__init__()

self.base_model = base_model

# Optionally freeze the base model (only train the value head)

if freeze_base:

for param in self.base_model.parameters():

param.requires_grad = False

# Value head: converts hidden state → scalar reward

# (Just a linear layer with dropout for regularization)

self.value_head = nn.Sequential(

nn.Dropout(0.1), # Prevent overfitting

nn.Linear(hidden_size, 1) # hidden_size → 1 number

)

def forward(self, input_ids, attention_mask):

"""

Compute reward for an input sequence.

Args:

input_ids: Token IDs for [prompt] [response]

attention_mask: 1 for real tokens, 0 for padding

Returns:

reward: Scalar score for this prompt-response pair

"""

# Step 1: Run the base model to get hidden states

outputs = self.base_model(

input_ids=input_ids,

attention_mask=attention_mask,

output_hidden_states=True

)

# Step 2: Get the last hidden state

# Shape: (batch_size, sequence_length, hidden_size)

hidden_states = outputs.last_hidden_state

# Step 3: Extract the hidden state at the LAST non-padding token

# Why the last token? It's "seen" the entire prompt + response,

# so it has all the context needed to judge quality.

# Find the position of the last real token for each sequence

seq_lengths = attention_mask.sum(dim=1) - 1 # -1 for 0-indexing

# Index into the hidden states to grab that last position

batch_size = hidden_states.shape[0]

last_hidden = hidden_states[

torch.arange(batch_size),

seq_lengths.long()

]

# Step 4: Pass through value head to get scalar reward

reward = self.value_head(last_hidden).squeeze(-1)

return reward

# Create a reward model

print("Building a reward model from GPT-2...")

print()

model_name = "gpt2"

base_model = AutoModel.from_pretrained(model_name)

tokenizer = AutoTokenizer.from_pretrained(model_name)

tokenizer.pad_token = tokenizer.eos_token # GPT-2 doesn't have a pad token by default

reward_model = RewardModel(

base_model,

hidden_size=base_model.config.hidden_size,

freeze_base=False # Train everything

)

print(f"Reward model created.")

print()

print(f"Base model parameters: {sum(p.numel() for p in base_model.parameters()):,}")

print(f"Value head parameters: {sum(p.numel() for p in reward_model.value_head.parameters()):,}")

print()

print("That value head is tiny: just 769 parameters.")

print("(It's literally: 768-dimensional vector → 1 number)")

print("But it's enough to learn human preferences when combined with the base model.")Building a reward model from GPT-2...

Reward model created.

Base model parameters: 124,439,808

Value head parameters: 769

That value head is tiny: just 769 parameters.

(It's literally: 768-dimensional vector → 1 number)

But it's enough to learn human preferences when combined with the base model.

Testing the Reward Model¶

Let’s test our (untrained) reward model.

We’ll give it two responses to “What is 2+2?”:

A correct answer

An “I don’t know” response

Before training, the rewards will be random. The model hasn’t learned anything about preferences yet.

# Test forward pass with two responses

test_texts = [

"What is 2+2? The answer is 4.",

"What is 2+2? I don't know."

]

# Tokenize both responses

inputs = tokenizer(

test_texts,

padding=True, # Pad to same length

return_tensors="pt" # Return PyTorch tensors

)

# Run through the reward model

with torch.no_grad(): # Don't compute gradients (we're just testing)

rewards = reward_model(

input_ids=inputs["input_ids"],

attention_mask=inputs["attention_mask"]

)

print("Reward scores (before training):")

print("=" * 60)

for text, reward in zip(test_texts, rewards):

print(f" '{text}' → {reward.item():.4f}")

print()

print("The rewards are random.")

print("The model has no idea that the first response is better.")

print()

print("After training on preference data, we'd expect:")

print(" - First response (correct answer): HIGH reward")

print(" - Second response (unhelpful): LOW reward")Reward scores (before training):

============================================================

'What is 2+2? The answer is 4.' → 2.8958

'What is 2+2? I don't know.' → 1.1211

The rewards are random.

The model has no idea that the first response is better.

After training on preference data, we'd expect:

- First response (correct answer): HIGH reward

- Second response (unhelpful): LOW reward

The Training Objective¶

We’ve got the architecture. Now: how do we train it?

We have preference data: lots of examples where humans said “Response A is better than Response B” for some prompt.

Our goal: teach the model to assign higher rewards to preferred responses.

We do this with the ranking loss (also called the “preference loss”):

Breaking it down:

is the loss we’re minimizing

means “expected value over...” (in practice: average over all training examples)

is one training example: a prompt , winning response , and losing response

is the natural logarithm

is sigmoid

is the difference in rewards

So: “The loss is the negative log probability that we assign the correct preference.”

We negate it because we minimize loss. Maximizing log probability = minimizing negative log probability.

Intuitively:

If (we correctly ranked the winner higher), the loss is LOW

If (we got it backwards), the loss is HIGH. The gradient will push up and down.

If (we’re not sure), the loss is medium. We’ll adjust the rewards to be more confident.

The clean thing about this loss: it doesn’t care about the absolute values of rewards, only the differences. The model can scale its rewards however it wants, as long as the rankings are correct.

Next Steps¶

We’ve covered the theory. Now we make it real.

In the following notebooks:

Preference Data: Where does this data come from? What does it look like? How do we format it?

Training: Complete implementation of the training loop. We’ll train a reward model.

Evaluation: How do you know if your reward model is good? (Accuracy alone isn’t enough. we need to watch for reward hacking.)