Every image you’ve ever seen from Stable Diffusion, Midjourney, or DALL-E started as pure random noise. A generative model learned to transform that noise into coherent images. In this notebook, we’ll build one from scratch.

We’ll use flow matching - a simple approach that has become the foundation for state-of-the-art image generation. By the end, you’ll have a model that can generate handwritten digits from nothing but Gaussian noise.

The Problem We’re Solving¶

Here’s the setup:

We have training data (real MNIST digits)

We want to sample new images from

But we don’t know explicitly - we only have examples

The strategy: learn a transformation from a simple distribution (Gaussian noise) to our complex data distribution. If we can learn this transformation, we can generate new samples by:

Sample noise

Apply our learned transformation

Out comes a realistic image!

Why Flow Matching?¶

Several approaches exist for generative modeling:

| Approach | Core Idea | Challenge |

|---|---|---|

| GANs | Generator fools discriminator | Training instability, mode collapse |

| VAEs | Encode/decode through latent space | Blurry outputs, approximate posteriors |

| DDPM | Gradually denoise over many steps | Stochastic, slow sampling, complex math |

| Flow Matching | Learn straight paths from noise to data | Simple, fast, deterministic |

Flow matching has become the preferred choice because:

Simpler mathematics - no stochastic differential equations required

Faster sampling - straight paths require fewer integration steps

Same training objective works for any architecture

State-of-the-art results - used in Stable Diffusion 3, Flux, and more

The Mathematical Framework¶

Probability Paths: The Core Intuition¶

Imagine two probability distributions:

: The data distribution (complex, what we want to sample from)

: A simple distribution (standard Gaussian, easy to sample)

Flow matching constructs a continuous path of distributions that smoothly transitions between them:

The key insight: if we can describe how individual samples move along this path, we can:

Train: Learn the “velocity” of samples at each point

Generate: Start from (noise) and follow velocities backward to (data)

Linear Interpolation: The Simplest Path¶

How do we connect a data point to a noise sample ? The simplest choice is a straight line:

Let’s verify this gives us what we want:

| Description | ||

|---|---|---|

| 0 | Pure data | |

| 0.5 | Half data, half noise | |

| 1 | Pure noise |

Perfect. As goes from 0 to 1, we trace a straight line from the data point to the noise sample.

(This linear path is sometimes called rectified flow or optimal transport flow, because straight lines are the shortest paths between points.)

The Velocity Field¶

The velocity tells us how changes as increases. Let’s derive it:

Taking the derivative term by term:

This result is remarkable: the velocity is constant! It doesn’t depend on at all.

Why does this matter?

Each sample travels in a perfectly straight line

The velocity is simply the direction from data to noise

No curved paths, no acceleration - just constant motion

The Neural Network’s Job¶

We train a neural network to predict the velocity given:

: The current “noised” sample (a blend of data and noise)

: The current timestep

The training loss is straightforward MSE:

In words: sample data, sample noise, sample timestep, compute the interpolation , predict velocity, compare to true velocity .

Generating Samples: Solving the ODE¶

Once trained, generation is an ordinary differential equation (ODE):

We start at with pure noise and integrate backward to :

In practice, we use Euler integration:

Starting at , we take small steps backward until we reach .

Key Equations at a Glance¶

| Concept | Equation | What It Does |

|---|---|---|

| Interpolation | Creates path from data to noise | |

| Velocity | Direction of travel (constant!) | |

| Training Loss | MSE between predicted and true velocity | |

| Sampling ODE | Defines the generation dynamics | |

| Euler Step | Discrete approximation for sampling |

Now let’s implement this.

import torch

import torch.nn as nn

import torchvision

import torchvision.transforms as transforms

from torch.utils.data import DataLoader

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

# Auto-reload modules during development

%load_ext autoreload

%autoreload 2

# Set up device

if torch.cuda.is_available():

device = torch.device("cuda")

elif torch.backends.mps.is_available():

device = torch.device("mps")

else:

device = torch.device("cpu")

print(f"Using device: {device}")Using device: cuda

Step 1: The Data Distribution¶

We’ll use MNIST - 28×28 grayscale handwritten digits. It’s ideal for learning:

Small images (784 pixels) = fast training

Simple enough to verify visually

Complex enough to be interesting (10 digit classes, varying styles)

Important preprocessing: We normalize pixels to instead of . Why? Our noise distribution is centered at zero with values typically in . Centering our data similarly makes the interpolation path more balanced.

# Transform: convert to tensor and normalize to [-1, 1]

transform = transforms.Compose([

transforms.ToTensor(),

transforms.Normalize((0.5,), (0.5,)) # Maps [0,1] to [-1,1]

])

# Download and load MNIST

train_dataset = torchvision.datasets.MNIST(

root="./data",

train=True,

download=True,

transform=transform

)

train_loader = DataLoader(

train_dataset,

batch_size=128,

shuffle=True,

num_workers=0, # Set to 0 for MPS compatibility

drop_last=True

)

print(f"Dataset size: {len(train_dataset):,} images")

print(f"Batches per epoch: {len(train_loader)}")

print(f"Image shape: {train_dataset[0][0].shape}")

print(f"Pixel range: [{train_dataset[0][0].min():.1f}, {train_dataset[0][0].max():.1f}]")Dataset size: 60,000 images

Batches per epoch: 468

Image shape: torch.Size([1, 28, 28])

Pixel range: [-1.0, 1.0]

# Visualize some training samples

def show_images(images, nrow=8, title=""):

"""Display a grid of images."""

# Denormalize from [-1, 1] to [0, 1]

images = (images + 1) / 2

images = images.clamp(0, 1)

grid = torchvision.utils.make_grid(images, nrow=nrow, padding=2)

plt.figure(figsize=(12, 12 * grid.shape[1] / grid.shape[2]))

plt.imshow(grid.permute(1, 2, 0).cpu().numpy(), cmap='gray')

plt.axis('off')

if title:

plt.title(title, fontsize=14)

plt.show()

# Get a batch and visualize

sample_batch, _ = next(iter(train_loader))

show_images(sample_batch[:32], title="Training samples from $p_{data}$ (MNIST digits)")

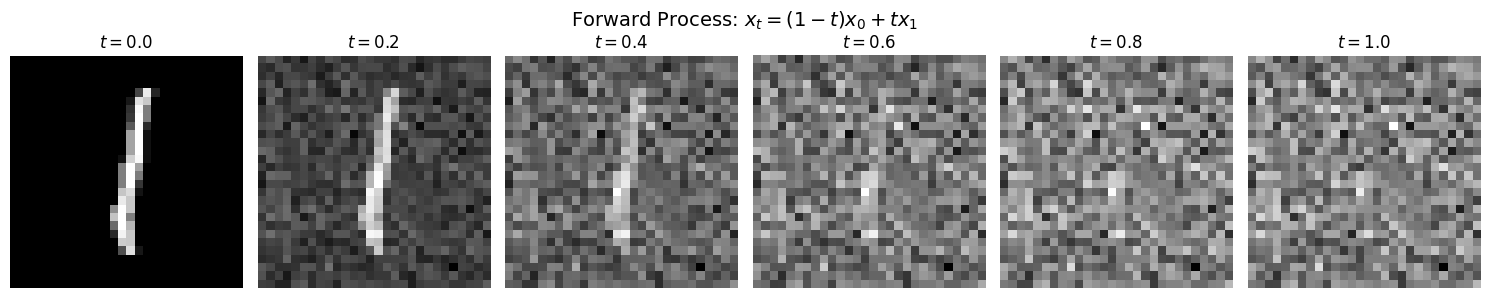

Step 2: The Forward Process (Data → Noise)¶

Let’s implement and visualize the interpolation path from data to noise.

The Interpolation Formula¶

For a data point and noise sample :

Geometric Picture¶

Think of each image as a point in 784-dimensional space (one dimension per pixel):

lives on the “data manifold” - the region where realistic digits reside

is a random point in space (Gaussian noise spreads throughout)

traces a straight line between them

During training, we’ll show the network samples at random timesteps and ask it to predict which direction leads toward noise.

from from_noise_to_images.flow import FlowMatching

flow = FlowMatching()

# Take one image and show its path to noise

x_0 = sample_batch[0:1] # Shape: (1, 1, 28, 28)

x_1 = torch.randn_like(x_0) # Sample noise ~ N(0, I)

# Show interpolation at different timesteps

timesteps = [0.0, 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, 1.0]

interpolated = []

for t in timesteps:

t_tensor = torch.tensor([t])

x_t, velocity = flow.forward_process(x_0, x_1, t_tensor)

interpolated.append(x_t)

# Visualize

fig, axes = plt.subplots(1, len(timesteps), figsize=(15, 3))

for i, (ax, t) in enumerate(zip(axes, timesteps)):

img = (interpolated[i][0, 0] + 1) / 2 # Denormalize

ax.imshow(img.numpy(), cmap='gray')

ax.set_title(f'$t = {t}$', fontsize=12)

ax.axis('off')

# Add equation annotation

if t == 0.0:

ax.set_xlabel('$x_0$ (data)', fontsize=10)

elif t == 1.0:

ax.set_xlabel('$x_1$ (noise)', fontsize=10)

elif t == 0.5:

ax.set_xlabel('$0.5 x_0 + 0.5 x_1$', fontsize=10)

plt.suptitle('Forward Process: $x_t = (1-t) x_0 + t x_1$', fontsize=14)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

print("\nWatch how the digit structure gradually dissolves into noise.")

print("Our model will learn to reverse this process.")

Watch how the digit structure gradually dissolves into noise.

Our model will learn to reverse this process.

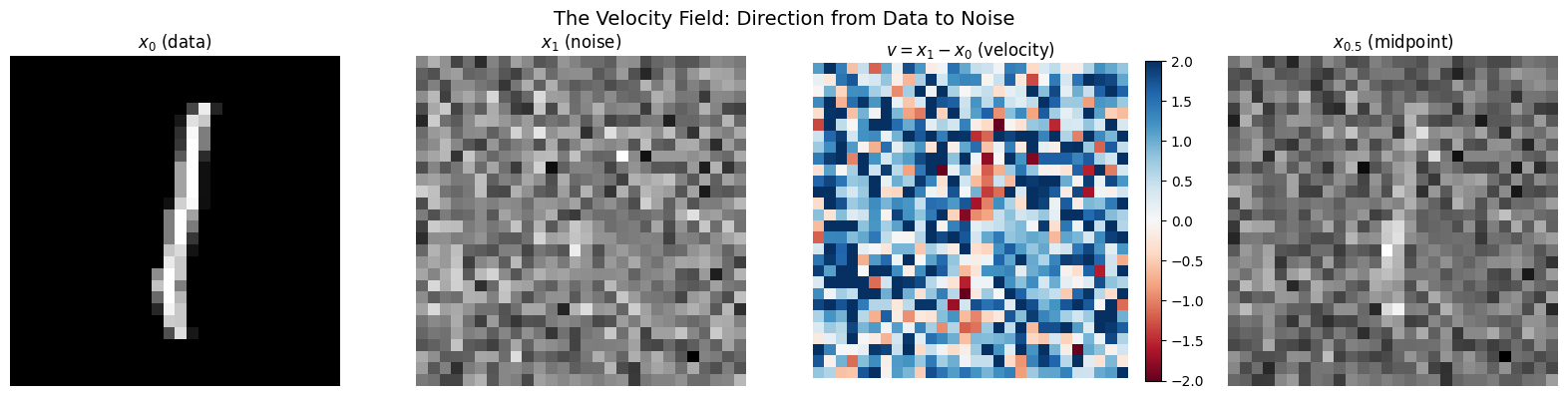

Step 3: Understanding the Velocity Field¶

Deriving the Velocity¶

The velocity is the time derivative of our interpolation:

Let’s work through this carefully:

Since and are constants (they don’t depend on ):

The Key Property: Constant Velocity¶

Notice that has no in it. This means:

| Property | Implication |

|---|---|

| Velocity is constant | Samples travel in straight lines |

| Same velocity at all | No acceleration, no curved paths |

| Velocity encodes the displacement from data to noise |

What Does the Velocity Look Like?¶

Since (pixel-wise subtraction):

Where noise is brighter than data (): positive velocity (pixel brightens)

Where noise is darker than data (): negative velocity (pixel darkens)

The velocity is essentially a “difference image”

# Compute and visualize the velocity field for a single example

t_tensor = torch.tensor([0.5]) # Timestep doesn't matter for velocity!

x_t, velocity = flow.forward_process(x_0, x_1, t_tensor)

fig, axes = plt.subplots(1, 4, figsize=(16, 4))

# Data point x_0

axes[0].imshow((x_0[0, 0] + 1) / 2, cmap='gray')

axes[0].set_title('$x_0$ (data)', fontsize=12)

axes[0].axis('off')

# Noise point x_1

axes[1].imshow((x_1[0, 0] + 1) / 2, cmap='gray')

axes[1].set_title('$x_1$ (noise)', fontsize=12)

axes[1].axis('off')

# Velocity v = x_1 - x_0

v_display = velocity[0, 0].numpy()

im = axes[2].imshow(v_display, cmap='RdBu', vmin=-2, vmax=2)

axes[2].set_title('$v = x_1 - x_0$ (velocity)', fontsize=12)

axes[2].axis('off')

plt.colorbar(im, ax=axes[2], fraction=0.046)

# Interpolated sample at t=0.5

axes[3].imshow((x_t[0, 0] + 1) / 2, cmap='gray')

axes[3].set_title('$x_{0.5}$ (midpoint)', fontsize=12)

axes[3].axis('off')

plt.suptitle('The Velocity Field: Direction from Data to Noise', fontsize=14)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

print("\nInterpreting the velocity:")

print("• Red: noise brighter than data → positive velocity")

print("• Blue: noise darker than data → negative velocity")

print("• White: similar values → near-zero velocity")

Interpreting the velocity:

• Red: noise brighter than data → positive velocity

• Blue: noise darker than data → negative velocity

• White: similar values → near-zero velocity

# Verify: velocity is constant at all timesteps

print("Verifying that velocity is constant along the path...")

print()

for t in [0.0, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1.0]:

t_tensor = torch.tensor([t])

_, v = flow.forward_process(x_0, x_1, t_tensor)

v_norm = torch.norm(v).item()

print(f"t = {t:.2f}: ||v|| = {v_norm:.4f}")

print()

print("✓ Velocity norm is identical at all timesteps!")

print(" This confirms v = x₁ - x₀ doesn't depend on t.")Verifying that velocity is constant along the path...

t = 0.00: ||v|| = 37.8678

t = 0.25: ||v|| = 37.8678

t = 0.50: ||v|| = 37.8678

t = 0.75: ||v|| = 37.8678

t = 1.00: ||v|| = 37.8678

✓ Velocity norm is identical at all timesteps!

This confirms v = x₁ - x₀ doesn't depend on t.

Step 4: The Neural Network Architecture¶

We need a neural network that:

Input: Noised image (28×28×1) + timestep (scalar)

Output: Predicted velocity (28×28×1, same shape as input)

U-Net: The Classic Choice¶

We use a U-Net, a proven architecture for image-to-image tasks:

Input (28×28) ──┐ ┌── Output (28×28)

▼ ▲

[Encoder] [Decoder]

│ │

downsample upsample

│ │

▼ ▲

(14×14) ──────────> (14×14) ← skip connection

│ │

downsample upsample

│ │

▼ ▲

(7×7) ──────────> (7×7) ← skip connection

│ │

└─────> bottleneck ────┘Why U-Net? The skip connections let fine-grained details flow directly to the output, while the bottleneck captures global context.

Timestep Conditioning¶

The network needs to know the current timestep . A scalar isn’t expressive enough, so we use sinusoidal positional encoding (from the Transformer paper):

where spans multiple frequencies. This rich embedding is projected and added to the network’s feature maps at each layer.

from from_noise_to_images.models import SimpleUNet

model = SimpleUNet(

in_channels=1, # Grayscale images

model_channels=64, # Base channel count (doubled at each level)

time_emb_dim=128, # Timestep embedding dimension

).to(device)

# Count parameters

num_params = sum(p.numel() for p in model.parameters() if p.requires_grad)

print(f"Model parameters: {num_params:,}")

print(f"\nThis is relatively small - larger models give better quality.")

# Test forward pass

test_x = torch.randn(4, 1, 28, 28, device=device)

test_t = torch.rand(4, device=device)

with torch.no_grad():

test_out = model(test_x, test_t)

print(f"\nForward pass test:")

print(f" Input shape: {test_x.shape} (batch, channels, height, width)")

print(f" Timestep: {test_t.shape} (batch,)")

print(f" Output shape: {test_out.shape} (same as input - velocity at each pixel)")Model parameters: 1,837,185

This is relatively small - larger models give better quality.

Forward pass test:

Input shape: torch.Size([4, 1, 28, 28]) (batch, channels, height, width)

Timestep: torch.Size([4]) (batch,)

Output shape: torch.Size([4, 1, 28, 28]) (same as input - velocity at each pixel)

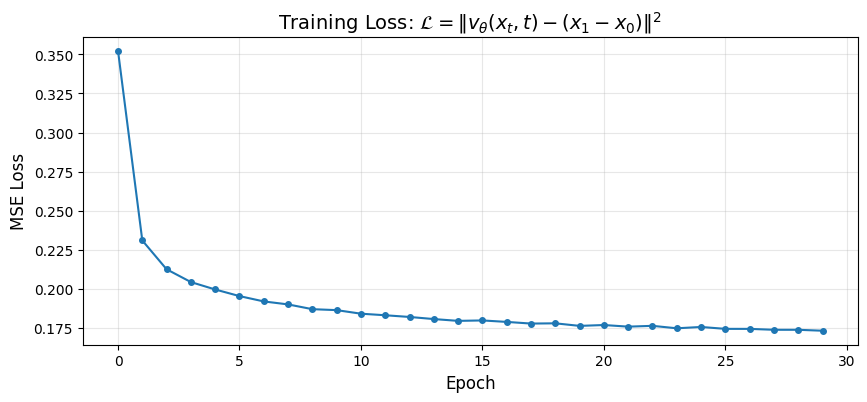

Step 5: Training the Velocity Predictor¶

The Training Loop¶

For each training step:

Sample data: (batch of real digits)

Sample noise: (same shape as )

Sample timestep:

Compute interpolation:

Compute true velocity:

Predict velocity:

Compute loss: (MSE)

Update weights: Backprop and optimizer step

Why Does This Work?¶

The model sees many triplets :

Different data points

Different noise samples

Different timesteps

It learns patterns like:

“At (mostly noise), velocities point toward structure”

“At (mostly data), velocities are small adjustments”

The key insight: by learning the conditional expectation of velocity given and , the model implicitly learns the marginal distribution at each timestep.

(There’s deep theory here connecting to optimal transport and continuity equations, but the practical algorithm is simple.)

from from_noise_to_images.train import Trainer

# Create trainer

trainer = Trainer(

model=model,

dataloader=train_loader,

lr=1e-4, # Learning rate

weight_decay=0.01, # Regularization

device=device,

)

# Train

NUM_EPOCHS = 30 # Increase to 50+ for better quality

print("Training the velocity prediction network...")

print(f"Epochs: {NUM_EPOCHS}")

print(f"Batch size: {train_loader.batch_size}")

print(f"Batches per epoch: {len(train_loader)}")

print()

losses = trainer.train(num_epochs=NUM_EPOCHS)Training the velocity prediction network...

Epochs: 30

Batch size: 128

Batches per epoch: 468

Training on cuda

Model parameters: 1,837,185

Epoch 1: avg_loss = 0.3523

Epoch 2: avg_loss = 0.2310

Epoch 3: avg_loss = 0.2126

Epoch 4: avg_loss = 0.2044

Epoch 5: avg_loss = 0.1997

Epoch 6: avg_loss = 0.1955

Epoch 7: avg_loss = 0.1921

Epoch 8: avg_loss = 0.1902

Epoch 9: avg_loss = 0.1871

Epoch 10: avg_loss = 0.1865

Epoch 11: avg_loss = 0.1842

Epoch 12: avg_loss = 0.1832

Epoch 13: avg_loss = 0.1821

Epoch 14: avg_loss = 0.1808

Epoch 15: avg_loss = 0.1796

Epoch 16: avg_loss = 0.1799

Epoch 17: avg_loss = 0.1790

Epoch 18: avg_loss = 0.1779

Epoch 19: avg_loss = 0.1781

Epoch 20: avg_loss = 0.1764

Epoch 21: avg_loss = 0.1770

Epoch 22: avg_loss = 0.1760

Epoch 23: avg_loss = 0.1765

Epoch 24: avg_loss = 0.1749

Epoch 25: avg_loss = 0.1757

Epoch 26: avg_loss = 0.1745

Epoch 27: avg_loss = 0.1745

Epoch 28: avg_loss = 0.1739

Epoch 29: avg_loss = 0.1739

Epoch 30: avg_loss = 0.1734

# Plot training loss

plt.figure(figsize=(10, 4))

plt.plot(losses, marker='o', markersize=4)

plt.xlabel('Epoch', fontsize=12)

plt.ylabel('MSE Loss', fontsize=12)

plt.title(r'Training Loss: $\mathcal{L} = \|v_\theta(x_t, t) - (x_1 - x_0)\|^2$', fontsize=14)

plt.grid(True, alpha=0.3)

plt.show()

print(f"Final loss: {losses[-1]:.4f}")

print("\nLower loss = better velocity predictions = better generation.")

Final loss: 0.1734

Lower loss = better velocity predictions = better generation.

Step 6: Generating New Images¶

using our trained model to generate new digits from scratch!

The Sampling ODE¶

We solve:

Starting point: (pure random noise at )

Goal: Integrate backward to to get a sample from

Euler Integration¶

We discretize time into steps with :

At each step:

Ask the model: “What’s the velocity at this point?”

Move in the opposite direction (we’re going backward in time)

Repeat until we reach

Why Backward?¶

During training, velocities point from data to noise ().

During sampling, we want the reverse - from noise to data - so we:

Start at (noise)

Subtract the velocity (opposite direction)

End at (data)

from from_noise_to_images.sampling import sample

# Generate samples

model.eval()

print("Generating 64 new digits from random noise...")

print("(Starting at t=1, integrating backward to t=0)")

print()

with torch.no_grad():

generated, trajectory = sample(

model=model,

num_samples=64,

image_shape=(1, 28, 28),

num_steps=50, # Number of Euler steps

device=device,

return_trajectory=True,

)

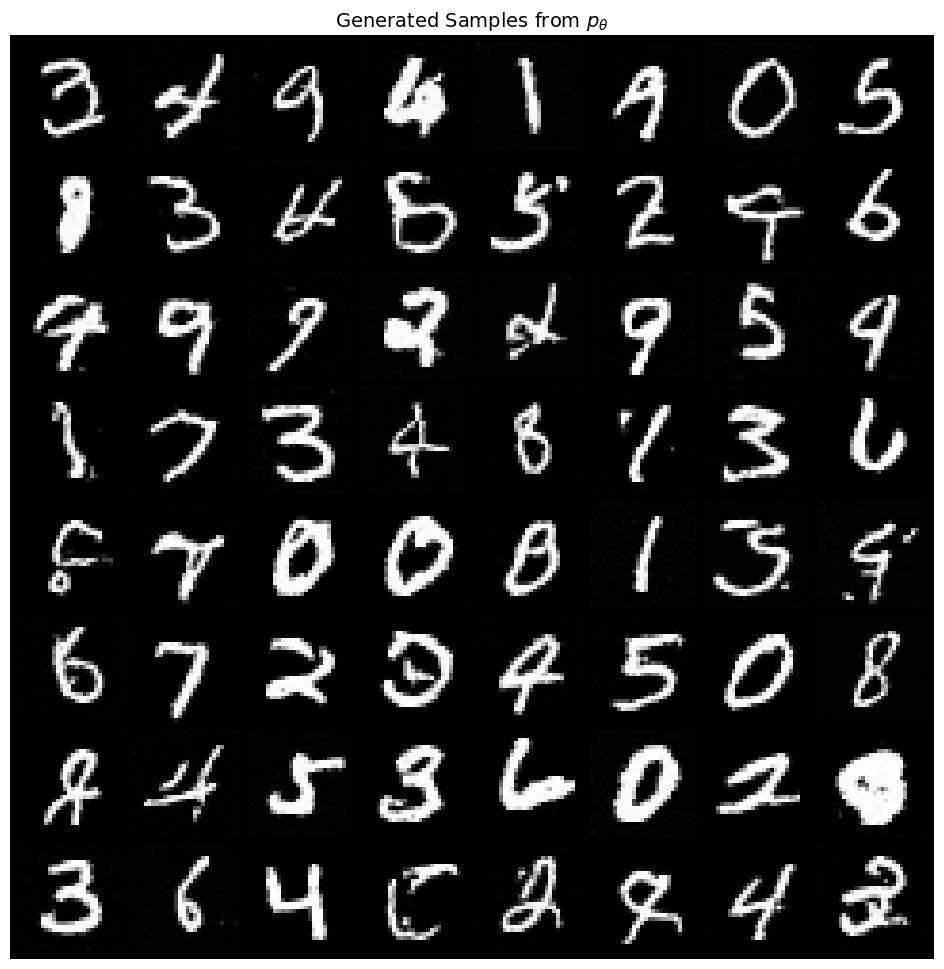

show_images(generated, nrow=8, title="Generated Samples from $p_{\\theta}$")Generating 64 new digits from random noise...

(Starting at t=1, integrating backward to t=0)

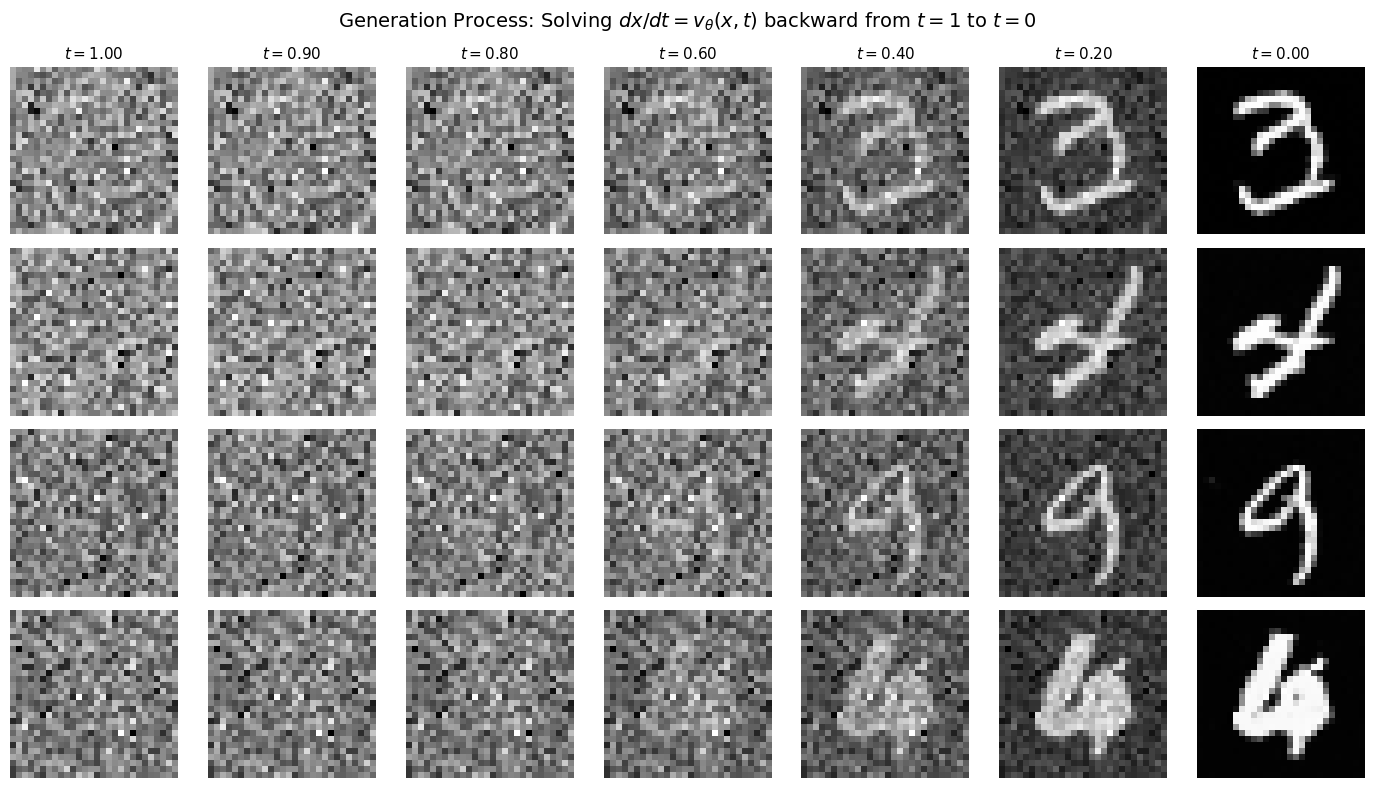

Step 7: Visualizing the Generation Process¶

Let’s watch how noise transforms into digits step by step.

This shows the ODE integration in action:

: Pure noise

: Following backward

: Generated digit

# Show the trajectory for a few samples

num_to_show = 4

steps_to_show = [0, 5, 10, 20, 30, 40, 50] # Which steps to visualize

fig, axes = plt.subplots(num_to_show, len(steps_to_show), figsize=(14, 8))

for row in range(num_to_show):

for col, step_idx in enumerate(steps_to_show):

img = trajectory[step_idx][row, 0]

img = (img + 1) / 2 # Denormalize

axes[row, col].imshow(img.cpu().numpy(), cmap='gray')

axes[row, col].axis('off')

if row == 0:

t_val = 1.0 - step_idx / 50

axes[row, col].set_title(f'$t={t_val:.2f}$', fontsize=11)

plt.suptitle('Generation Process: Solving $dx/dt = v_\\theta(x, t)$ backward from $t=1$ to $t=0$', fontsize=14)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

print("\nWatch how structure emerges:")

print("• t≈1.0: Random noise (no discernible pattern)")

print("• t≈0.6: Large-scale structure appears (rough digit shape)")

print("• t≈0.3: Details emerge (strokes, curves)")

print("• t=0.0: Final digit")

Watch how structure emerges:

• t≈1.0: Random noise (no discernible pattern)

• t≈0.6: Large-scale structure appears (rough digit shape)

• t≈0.3: Details emerge (strokes, curves)

• t=0.0: Final digit

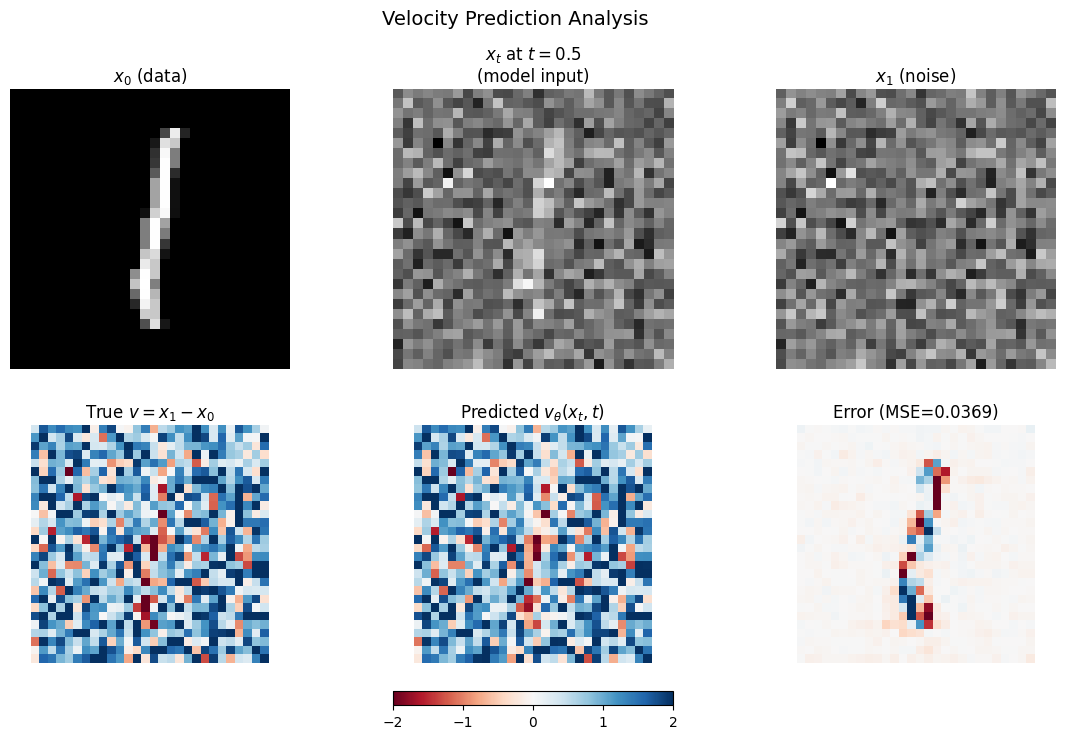

Step 8: Analyzing What the Model Learned¶

Let’s examine how well the model predicts velocities. Remember: the model only sees and , but must predict . It can’t know the exact used (since that’s random), so it learns to predict the expected velocity given the noisy input.

# Compare predicted vs true velocity

x_0 = sample_batch[0:1].to(device)

x_1 = torch.randn_like(x_0)

t = torch.tensor([0.5], device=device)

# True velocity

true_v = x_1 - x_0

# Interpolated sample

x_t = (1 - t.view(-1, 1, 1, 1)) * x_0 + t.view(-1, 1, 1, 1) * x_1

# Predicted velocity

model.eval()

with torch.no_grad():

pred_v = model(x_t, t)

# Visualize

fig, axes = plt.subplots(2, 3, figsize=(14, 8))

# Top row: the samples

axes[0, 0].imshow((x_0[0, 0].cpu() + 1) / 2, cmap='gray')

axes[0, 0].set_title('$x_0$ (data)', fontsize=12)

axes[0, 0].axis('off')

axes[0, 1].imshow((x_t[0, 0].cpu() + 1) / 2, cmap='gray')

axes[0, 1].set_title('$x_t$ at $t=0.5$\n(model input)', fontsize=12)

axes[0, 1].axis('off')

axes[0, 2].imshow((x_1[0, 0].cpu() + 1) / 2, cmap='gray')

axes[0, 2].set_title('$x_1$ (noise)', fontsize=12)

axes[0, 2].axis('off')

# Bottom row: velocities

vmin, vmax = -2, 2

im = axes[1, 0].imshow(true_v[0, 0].cpu(), cmap='RdBu', vmin=vmin, vmax=vmax)

axes[1, 0].set_title('True $v = x_1 - x_0$', fontsize=12)

axes[1, 0].axis('off')

axes[1, 1].imshow(pred_v[0, 0].cpu(), cmap='RdBu', vmin=vmin, vmax=vmax)

axes[1, 1].set_title('Predicted $v_\\theta(x_t, t)$', fontsize=12)

axes[1, 1].axis('off')

error = (pred_v - true_v)[0, 0].cpu()

axes[1, 2].imshow(error, cmap='RdBu', vmin=-1, vmax=1)

axes[1, 2].set_title(f'Error (MSE={torch.mean(error**2):.4f})', fontsize=12)

axes[1, 2].axis('off')

plt.colorbar(im, ax=axes[1, :], orientation='horizontal', fraction=0.05, pad=0.1)

plt.suptitle('Velocity Prediction Analysis', fontsize=14)

plt.show()

print("\nThe model sees only x_t and t, but must predict v = x_1 - x_0.")

print("It can't know the exact x_1 used, so it predicts the expected velocity.")

print("The prediction captures overall structure even if not pixel-perfect.")

The model sees only x_t and t, but must predict v = x_1 - x_0.

It can't know the exact x_1 used, so it predicts the expected velocity.

The prediction captures overall structure even if not pixel-perfect.

# Save the trained model for use in the next notebook

trainer.save_checkpoint("phase1_model.pt")

print("Model saved to phase1_model.pt")Model saved to phase1_model.pt

Summary: The Flow Matching Recipe¶

We’ve built a complete generative model using flow matching. Here’s the recipe:

The Framework¶

| Step | What Happens |

|---|---|

| 1. Define the path | Linear interpolation |

| 2. Compute velocity | Constant |

| 3. Train | Learn via MSE |

| 4. Sample | Solve ODE backward from to |

Key Mathematical Insights¶

| Concept | Why It Matters |

|---|---|

| Linear interpolation | Simplest path, constant velocity, optimal transport |

| Constant velocity | No acceleration = efficient integration |

| MSE loss | Directly measures velocity prediction quality |

| Deterministic ODE | Unlike DDPM, no stochastic noise during sampling |

Limitations (So Far)¶

Unconditional: We can’t control which digit gets generated

CNN architecture: U-Net works but doesn’t scale as well as transformers

Small scale: More training and larger models would help quality

What’s Next¶

In the following notebooks, we’ll address these limitations:

Notebook 02: Diffusion Transformer (DiT)

Replace the U-Net with a transformer

Patchify images into sequences

Use adaptive layer normalization (adaLN) for conditioning

Notebook 03: Class Conditioning

Control which digit gets generated

Classifier-free guidance for stronger conditioning

Notebook 04: Text Conditioning

CLIP text encoder integration

Cross-attention for text-to-image

Notebook 05: Latent Diffusion

Work in compressed latent space

VAE encoder/decoder

The Stable Diffusion approach